CBC: Does the deep state exist? Journalist Bruce Livesey investigates

By Bruce Livesey

Is Donald Trump facing impeachment because of the “deep state”?

He and his supporters certainly think so, pointing to the parade of military officers, CIA personnel, former diplomats and other members of the U.S. government eager to testify against Trump over the Ukraine scandal.

“Another whistleblower coming in from the Deep State!” Trump tweeted in October, after learning that a foreign policy official with knowledge of the Ukraine matter was willing to testify.

The term “deep state” now appears in major media and is heard throughout Washington — whereas before, it was only whispered by nutty conspiracy theorists. In a recent New York Times feature,Trump’s War on the ‘Deep State’ Turns Against Him, the reporters examine how “the deep state has emerged from the shadows” to defy the White House’s efforts to stymie the march to impeachment.

Meanwhile, bookstores are stocking new volumes with “deep state” in the title. And a television thriller Deep State, refers to a president “who tweets like a teenage girl” while being undermined by sinister forces.

But what exactly is the so-called “deep state”? And does it really exist?

“For me, the deep state is a theatre or playing field of political actors operating behind the scenes, either in concert with, or in opposition to, state government policy,” said Professor Ryan Gingeras of the department of national security affairs at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif. to CBC Radio’s IDEAS.

“Different constituencies use it in different ways,” adds Nancy MacLean, historian at Duke University and author Democracy in Chains: the Deep History of the Radical Right’s Stealth Plan for America.

“For the most part it’s a term used by the political right… to signify those parts of the state that don’t fall into willing compliance with the president’s agenda.”

Yet many might be surprised to learn that the term originated in Turkey.

“The Republic of Turkey, in some respects, began as a conspiracy — a conspiracy within the Ottoman imperial army at the very end of the First World War,” said Gingeras, an authority on Turkey’s history.

‘Deep state’ origin

After the Turkish military began a series of coups starting in 1960, the term “deep state” emerged within Turkey to describe the army’s often powerful and stealthy role in governmental affairs.

“For the longest time, people [in Turkey] talked about the ‘deep state’ as if it was an actual institution within the Turkish government that operated behind the scenes,” Gingeras said.

“And it was an institution that was made up of lots of different actors, ranging from military officers to members of the intelligence community, elements of organized crime, as well as private citizens who operated in conjunction with one another to essentially negate government policy.”

The notion gained further credence in 1996 when a Mercedes sedan crashed into a truck on the outskirts of the small town of Sursuluk in western Turkey, killing three of its four passengers. Among the passengers was a deputy chief of Istanbul’s police department, a member of Turkey’s parliament, and Abdullah Çatlī, a contract killer for the Turkish secret service, a leader of the Grey Wolves terrorist organization and one of Europe’s most wanted men.

“In the subsequent investigation, it was discovered that Çatlī possessed a diplomatic passport under an assumed name, signed by the interior minister,” said Gingeras.

“[It] was discovered was that he been hired by the Turkish government to engage in a series of conspiratorial and violent acts, including murder… And it confirmed in people’s mind… a sort of shadow government or a shadow body was acting in the interest of the state. But in highly illegal and violent ways.”

Yet Turkey wasn’t the only Middle Eastern country where the idea of the “deep state” has been applied: in Egypt, after the military came to power in a 1952 coup which overthrew a parliamentary democracy, the term took root there as well. The military is the dominant power in Egyptian society, controlling not only security but most of its economy.

By 2011, the Hosni Mubarak regime had fallen into disrepute after years of corruption and failing to meet Egyptians’ basic needs. When the Arab Spring broke out that year, citizens took to the streets to demand the Mubarak family’s removal from power.

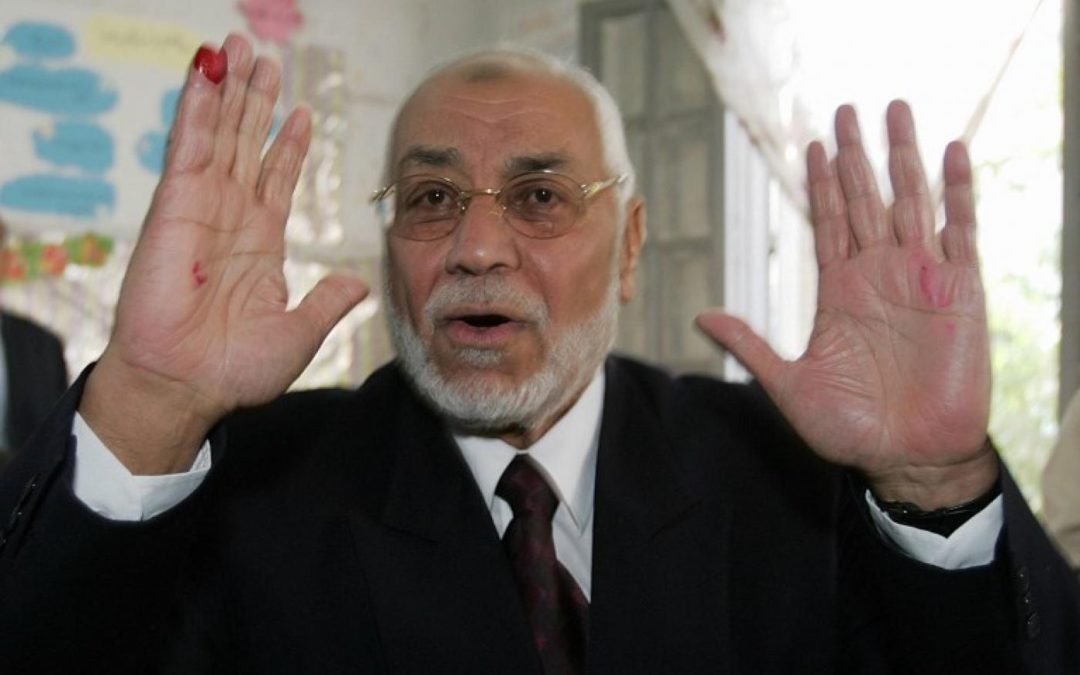

The following year, the Muslim Brotherhood’s candidate, Mohamed Morsi, was elected Egypt’s first new civilian president.

“The mistake that Egyptians made at the time is to believe that it was over, [that] the struggle to regain a free Egypt had succeeded,” said Dr. Wael Haddara, a Canadian physician and medical professor at Western University, who was a close advisor to Morsi.

“The mission was accomplished and so people lowered their guards. What had happened in reality is that the military, and to a lesser extent security forces, were just regrouping to regain the upper hand once more.”

Indeed, Haddara says the military quickly undermined Morsi’s capacity to rule. He not only didn’t control the military, he also didn’t control the judiciary, police or state media.

“The Minister of Finance withheld information about government finances, the governor of the Central Bank of Egypt refused to engage with mechanisms to secure financing from the IMF,” said Haddara.

“In fact, there were many acts of sabotage throughout the year he was in office.”

With Morsi facing growing unrest in the streets, the Egyptian military initiated a coup in July 2013, and installed Morsi’s defence secretary, General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, as new ruler. Morsi was arrested on charges of espionage, and in his subsequent trial in the summer of 2019, collapsed and died.

‘War merchants’

The journey of the term “deep state” to North America is a remarkable one. It didn’t fully arrive here until it was borrowed by an obscure Canadian-born academic, Peter Dale Scott, an English professor at the University of California in Berkeley.

Dale Scott was fascinated with the JFK’s assassination, the Vietnam War and 9/11, and became convinced that a so-called “deep state” played a determining role in these events. His books soon began finding an eager audience within elements of the emerging alt-right. Dale Scott was a repeat guest on Infowars, hosted by the far-right gadfly, Alex Jones.

Meanwhile, Steve Bannon, an itinerant former Goldman Sachs executive and documentary filmmaker, adopted the view that the “deep state” was undermining the capacity of the U.S. government to govern for the general population. He went seeking a candidate to run for president in 2016, focusing on Donald Trump, who embraced the same view.

But long before Trump’s arrival, the idea of secretive powers manipulating the U.S. government had been articulated by U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower. In his 1961 farewell address, he famously declared: “We have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions.”

Eisenhower went on to issue his prescient warning: “Now this conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence — economic, political, even spiritual — is felt in every city, every statehouse, every office of the federal government… We must not fail to comprehend its grave implications… In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex.”

Today, the U.S. arms industry is dominated by half a dozen of giant contractors such as Lockheed Martin, Raytheon and Boeing — all of which have factories in key Congressional districts.

“I call them war merchants, or merchants of war,” said Col. Lawrence Wilkerson, who served 31 years in the U.S. military, and was chief of staff for former Secretary of State Colin Powell. As he told IDEAS, “They have incredible influence over the national security decision-making and the foreign policy decision-making in Washington.”

Wilkerson says America’s involvement in wars, extending from Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq, to its current wars around the globe, is greatly due to the power of the military industrial complex.

But the rise of multinationals and globalization has also meant individual governments face enormous pressure to bow to their economic power. Many academics believe we are now living in the era of the “captured state”, wherein corporations now exert outsize influence behind the scenes on governments, and shape which policies and laws should be implemented.

The influence of James McGill Buchanan Jr.

Nancy MacLean, a historian at Duke University, has focused her research on the work of an obscure Nobel Prize-winning economist, James McGill Buchanan Jr., whose writings deeply affected Charles Koch, CEO of Koch Industries, a Kansas-based oil giant.

“[Buchanan] is probably the most influential thinker about democracy in our modern era,” said MacLean.

“And yet he is almost unknown to the public.”

MacLean says Buchanan was a libertarian who was opposed to government intervention in society, pressing for rescinding progressive laws, regulation, social programs and equity legislation.

MacLean documented how his ideas influenced Charles and his brother David Koch, who together built the powerful Koch political machine.

“The Koch political network now rivals the major political parties in the United States at election time,” said MacLean.

“It surpasses some of them in its funding and its operations. They fund quite literally hundreds of organizations.”

Canada falls prey to oil industry power

Indeed, much of the Trump agenda is borrowed from the Koch network, while key administration personnel used to work for it. But does this sort of corporate capture extend to Canada?

Kevin Taft, former leader of Alberta’s Liberal Party and the author of Oil’s Deep State, believes so. He’s documented the power the oil industry has on both the Alberta and federal governments.

“Part of the strategy for the industry is to focus on public institutions and turn those institutions into instruments of the industry,” Taft said.

He notes that even parties that were more critical of the energy sector, such as the NDP, fall prey to its power.

“It was really clear to me when I was in the legislature that the New Democrats were determined to hold the oil industry to account,” said Taft. “They called consistently for higher royalties, for better environmental standards and for more upgrading of the raw material in Alberta before it was shipped abroad.

“So I was really startled the night of the (2015) election victory for Rachel Notley when she immediately began making speeches about her friends in the oil industry and how she wanted a message to go out to the oil industry that everything was going to be OK, we were going to collaborate with them.”

Taft says the election of Stephen Harper in 2006 saw the oil industry gain its closest ally in the highest office in the land.

“Harper was closely tied and remains closely tied to Big Oil,” said Taft. “He would make no bones about it… How that played out over the years that he served as prime minister is that the portion of the federal civil service that has anything to do with the oil industry was brought closer and closer to the industry.”

After Justin Trudeau’s election in 2015, the new prime minister has also worked to allay the fears of the oil industry, in particular when he purchased the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipeline last year.

“The purchase of the Trans Mountain pipeline was just a sign to me of the raw flexing of the oil industry’s muscle,” Taft told IDEAS.

“The industry really really wants this pipeline. It wasn’t prepared to finance it itself, and yet it was able to put enough pressure to get the federal government to buy it for them.”

Original Link: https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/does-the-deep-state-exist-journalist-bruce-livesey-investigates-1.5363412