Mar 9, 2020

By Wael Haddara and Faisal Kutty

Last week 12 members of a German far–right group were arrested for plotting a large-scale attack on mosques similar to the ones carried out in New Zealand last year. At the same time, German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s chosen successor resigned as the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party leader because she could not stop party collaboration with the far–right, anti-Islam party, Alternative for Deutschland (AfD), to elect a state premier. The far–right ideological underpinnings of such hate groups now sit securely within many governments.

For years the threat of right-wing groups has been seen by law enforcement as their ability to commit terrorist acts like the Quebec Mosque shooting of 2017. Much research has also been published on how these groups have gained considerable influence by building an Islamophobia network of organizations and individuals who actively shape an anti-Muslim sentiment in national and international political discourse. There has also been significant exposure of their massive online disinformation campaigns. However, far less is known about the pervasiveness of far–right ideology in centers of authority and power – those which influence practices, policy, and direction of our government institutions. In Canada, the last several years have seen growing criticism of CSIS, RCMP, and CBSA for their discriminatory organizational cultures and whether these are developed intentionally or not, remains to be seen.

On one hand, it appears that the Government of Canada and its agencies recognize the far right threat and take it seriously. In August 2019, former Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale declared that the presence of right-wing extremism in Canada is real and dangerous. CSIS director David Vigneault echoed that the agency is “more and more preoccupied” with the threat of violent right-wing extremism and white supremacists. On the other hand, a leaked public safety presentation by CSIS and the RCMP recently called for “bias-free terminology” and generalizing the naming of the right-wing threat to “violent extremist groups” in order to obfuscate the true nature of the threat.

This tacit approval is especially concerning because outside of Canada, the far–right has legitimated its ideology by gaining control of security-related portfolios such as national intelligence, law enforcement, and military forces, usually through electoral successes. Among liberal Western countries, Austria represents one of the clearest examples of this trend. In 2018, Austria’s far–right Freedom Party (FPO), then in charge of the interior, foreign, and defense ministries, ordered a police raid of the domestic intelligence service after it refused to provide the names of informants embedded within far–right circles. This unprecedented raid revealed years’ worth of intelligence dossiers belonging to Austria and its allied nations. Similarly, Georg Maaßen, Germany’s ex-spy chief, was forcibly removed from office after public outcry over his far–right views.

In the United States, far–right infiltration of government and security agencies has been playing out at the highest political levels. Steve Bannon, Stephen Miller, Sebastian Gorka and Trump himself have all given the far–right a national platform. These political actors and others have emboldened racist members of security agencies who openly espouse their hatred on social media. The subsequent presence of far–right proponents in police, security agencies and the military should also come as no surprise. This unfortunate reality is well documented in the US, where extremist groups have infiltrated law enforcement and the military for training, experience, and access to weapons.

At home, the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) recently launched an investigation into one of its combat engineers for ties to “The Base”–a sister organization to the American neo-nazi group Atomwaffen Division. Similarly, a 2019 report by Canadian military intelligence revealed that since 2013, dozens of CAF members have had links to far–right groups including Atomwaffen, the Hammerskins Nation, Proud Boys, the Quebecois nationalist group La Meute, the anti-immigrant Soldiers of Odin, and a paramilitary militia called the III%.

Unlike CAF which has taken internal action, recent events demonstrate that other institutions continue to be home to racist, discriminatory and possibly xenophobic attitudes and players. David Vigneault of CSIS vowed to take “concrete steps” to create a “healthy and respectful” workplace only to have more complaints surface. When whistleblowers exposed the profiling of Muslim graduate students last year, Vigneault rejected the claims and stressed that Canadians must trust CSIS.

Existing attacks by far right groups can no longer be seen as isolated events. Further, tepid security responses to violent far–right extremism can not simply be an issue of bureaucratic inertia. These groups continue to publicly operate in Canadian institutions with minimal restraint. The evidence is plain to see. Our government must be held accountable to ensure that far–right ideology is removed from policies and practices of institutions that exist to serve and protect Canadians.

Oct 23, 2019

By Wael Haddara

Back in March, before the untimely passing of former Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi, I had written about his approach to foreign policy, which combined values with pragmatism and allowed for a delicate balance in the turbulent world of Middle East international affairs.

One of the examples I cited was his attempt to manage the conflict in Syria through a quartet composed of Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Iran. His rationale for including Iran was that it was a major and significant player in the Syrian conflict, and that it was essential to have it as part of the solution to avoid further escalation.

Confrontational approach

I received some critical feedback, namely that Morsi’s proposal was seen by the Saudis to be empowering Iran. At the time, Saudi leaders, though paying lip service to the idea of a quartet, persisted in obstructing any real work through this mechanism.

We now know that Saudi leaders favoured a confrontational, muscular approach to Iran, including the dismantling of the Iran nuclear deal, the enactment of further sanctions, and military strikes, all carried out by the US. All of this, of course, was before a strike on Saudi oil facilities resulted in the loss of half of that country’s oil production.

But back to Syria: six years after the coup that removed Morsi from office, Iran is among the key actors in Syria in control of the country. The ascendancy of Tehran has taken place despite an unfettered Saudi policy of regime change in Syria.

If the objective of excluding Iran from talks on the future of Syria was intended to weaken Iran, the course of action pursued by the Saudis has resulted in exactly the opposite – and Syria is not the only theatre where Saudi strategy on Iran has failed.

Losing the war

In Yemen, the Iran-supported Houthis recently claimed to have killed 500 Saudi soldiers and captured a staggering 2,000, in addition to equipment from a military convoy. Regardless of the veracity of that specific claim, it is clear that Saudi Arabia has lost the conflict in Yemen.

Saudi forces have engaged in acts of aggression alleged to be war crimes, and Saudi strategy has produced one of the worst humanitarian crises in theatres of war in modern times.

Lebanon is another country where Iran has leverage and where Saudi Arabia’s strategy to change the balance of power has failed – if kidnapping and forcing the prime minister’s resignation can be elevated to the level of strategy.

Saudi and Emirati foreign policy, including support for counter-revolutions across the Arab world, was ostensibly aimed at strengthening their domestic and regional positions. Saudi leaders seem to consider democratisation in general – and Islamists in particular – as the greatest threat to the stability of their regime, and indeed, a bigger threat than Iran.

A democratically elected government that could have leveraged Egypt’s natural strengths was removed, and societal cohesion was fractured in favour of a military authoritarian regime. The result has been a severely weakened Egypt, unable or unwilling to offer any support on regional conflicts.

Manifest failure

Now, the Saudis have been forced to accept that a belligerent approach to Iran is likely to be unproductive and unsustainable – or, as the Israeli newspaper Haaretz put it bluntly: “Saudi Arabia recognizes its weakness and is ready to talk to the Iranian foe.” But Riyadh now approaches these negotiations from a position of manifest failure: of its regional strategy, of its defences, and of its ability to develop an effective coalition.

Could things have been different? In 2012, there was a real potential for an effective axis against Iranian regional ambitions, with Turkey-Egypt-Saudi Arabia representing an overwhelming combination of population, wealth, military readiness and credibility. Yet, effective as that alliance might have been against Iran, it would eventually have highlighted the fact that one of the three countries remained mired in a mediaeval governance system.

Saudi Arabia has succeeded in its objective of aborting, or at least significantly impeding, the Arab Spring. But in the course of doing so, it has left itself vulnerable and weakened. It need not have been this way.

Original Link: https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/thwarting-arab-spring-riyadh-shot-itself-foot

Jul 18, 2019

Morsi was held in terrible and inhumane conditions since the Egyptian military overthrew his government close to six years ago. There had been many warnings about his deteriorating health, including from a British parliamentary delegation that visited Egypt last year. They concluded that, “If Morsi is not provided with adequate medical care soon, the consequences could be his premature death.” At 67, Morsi was relatively young, but the notorious so-called Scorpion Prison where he was held is less a prison and more a grave.

Not that Morsi did not understand the personal cost to challenging the military’s domination of political and public life in Egypt. In June 2012, he told an Egyptian television anchor that assuming executive authority in Egypt was a “kind of suicide.” In December of that year, he told me that if he were successful in navigating Egypt toward democracy, he expected to be assassinated. But his determination to serve his country despite the dangers does not diminish the shock and horror of his death. Now Morsi’s killers should be held accountable.

I was first introduced to Mohamed Morsi in May of 2012, shortly after he became the Freedom and Justice Party’s presidential candidate. Egypt had just gone through an unprecedented revolution, and hopes were high for a democratic future. I advised him on media and communications during the campaign, and we developed a very close relationship. After the campaign, I shuttled back and forth between Cairo and my home in Canada to assist with various issues. There were many failures during the year Morsi was in office, but also many successes. The former have been amplified by many, the latter muted.

Morsi was a deeply caring man, and in many ways, a successful statesman. He cared about his country and about Egyptians. He refused to implement drastic cuts to fuel and food subsidies that would have disproportionately affected the poor and the middle class. Instead, he directed his cabinet to focus on reforming the subsidy regime to eliminate corruption and improve benefits. His fight against corruption added to the forces arraigned against him. Corruption was and remains big business in Egypt.

Born in a village in rural Egypt, Morsi never lost a strong sense of connection with poor and struggling Egyptians. The Presidential Palace could host a delegation of tribal leaders from Sinai in the morning and then welcome Hillary Clinton or Catherine Ashton in the afternoon. Morsi could exist and move in both worlds, but his heart was firmly planted in Egyptian soil.

His death has significant implications. The military regime in Cairo still holds thousands of Egyptians in brutal conditions. It has already executed dozens, and its courts have sentenced thousands more to death. Europe and the United States are complicit in Morsi’s death through their support of the military regime. If they continue to be silent in the face of this crime, Egypt’s military dictatorship will be further emboldened, more people will be imprisoned and killed, and Egypt will fall further down into the abyss of oppression.

Moreover, Egypt’s rulers are not the only authoritarians watching the world’s reaction to Morsi’s death. The Sudanese and Algerians are watching, too, as they weigh how to extinguish their democracy movements.

At the end of the presidential campaign in 2012, I had no plans to return to Egypt. I had stumbled into politics and was intent on returning to my normal life as an academic and physician in Canada. Morsi would joke that it would be difficult for me to retreat from the front lines of world events. I told him that my secret plan was to have him sign an Egyptian flag, which I would then auction off when he became president.

Our last meeting during the campaign was in the early hours of June 15, 2012. As we prepared to go our separate ways, he turned to me and asked if I had brought a flag. Indeed, I had. His autograph reads, “The Egypt that lives in my imagination: An Egypt of values and civilization; an Egypt of growth and stability and love. And its flag, ever soaring above us.”

Sep 25, 2017

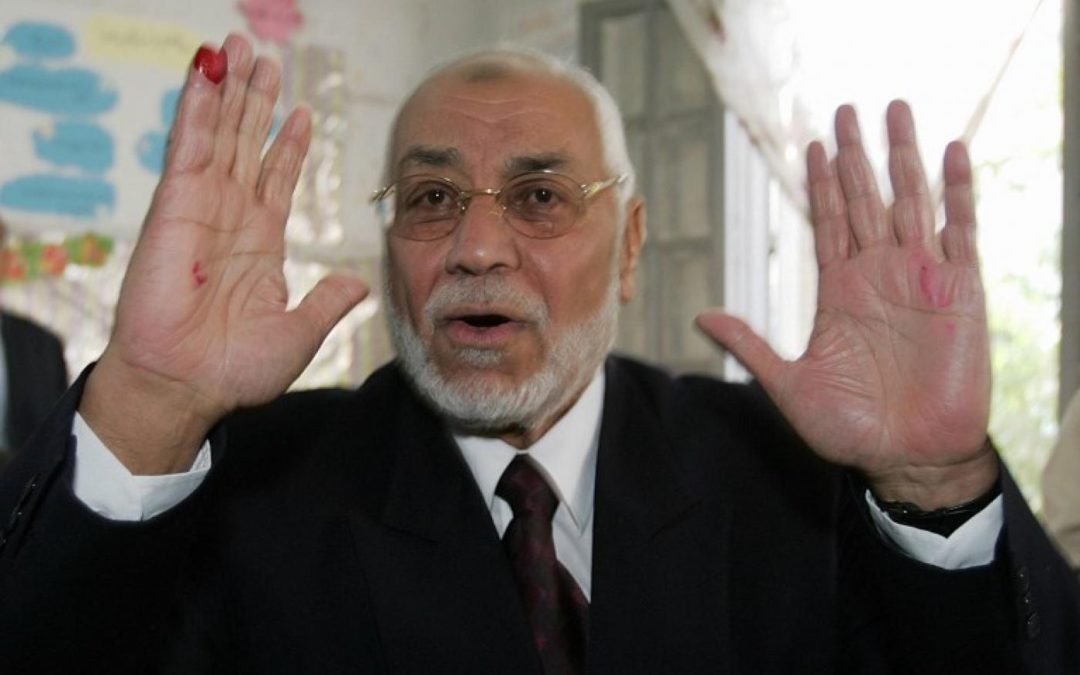

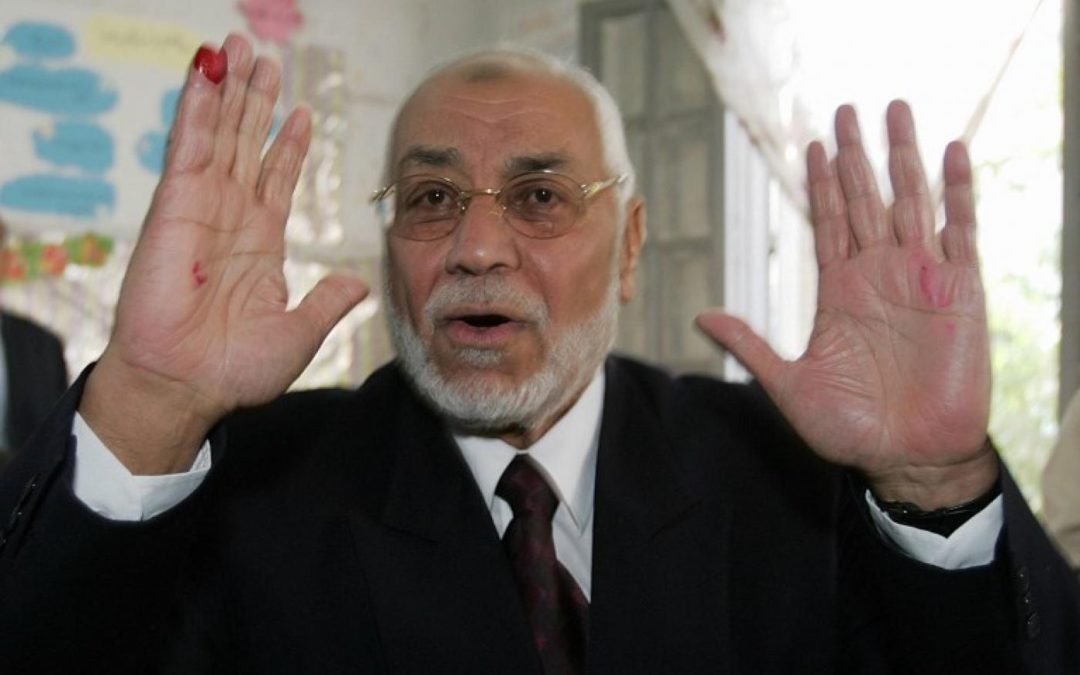

Photo: In November 2005, then Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohammed Mahdi Akef shows his finger, covered in ink after voting, as he walks away from a polling station a school in the populated suburb of Nasr City in Cairo (AFP)

Wael Haddara is an educator, associate professor of medicine at Western University, Canada, and a leader in the Canadian Muslim community. In 2012-2013, he served as senior advisor to President Mohamed Morsi of Egypt.

This month marks the 88th anniversary of the death of Omar Al-Mukhtar, the leader of the Libyan resistance to Italian occupation in the past century. Al-Mukhtar was executed for sedition by the occupying Italians on 16 September 1931.

In his famous eulogy of Al-Mukhtar, the celebrated poet Ahmad Shawqi predicted that his martyrdom would forever call Libyans to claim their freedom, and his blood would forever be an obstacle in the path of reconciliation between the occupier and the occupied.

It is a measure of the power of ideas and the impact of human resistance that when Al-Mukhtar was finally captured, at 73 years of age, the Italians chose to conduct his trial in secret and to bury him in an unmarked grave, guarded by an Italian sentry.

Oppressors are afraid of ideas, and of the men and women who believe in them, regardless of their frailty, advanced age or even whether they are dead or alive.

The frail man surrounded by security

This month also marks the death of another man, Mohammad Mahdi Akef. He was a former Egyptian parliamentarian, and the seventh man to serve as the general guide of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood.

Under his leadership in 2004, the Muslim Brotherhood issued the first truly comprehensive reform programme in Egypt, and in 2005 led the Muslim Brotherhood to its largest electoral victory prior to the 2011 Revolution.

In 2009, he was ranked as #12 in the 500 most influential Muslims, selected by scholars for a book issued by the Royal Islamic Center for Strategic Studies.

Following the overthrow of President Mohamed Morsi in 2013, he was arrested at the grand old age of 85 years and held, like many of Egypt’s 40,000 political prisoners, under brutal conditions.

According to his family, he was diagnosed with cancer last year, and despite declining health, was held, nearly incommunicado, by the Egyptian regime.

Akef was widely celebrated for refusing to be nominated for a second term as the Brotherhood’s guide, vacating the post in 2010 after the election of Muhammad Badie and he remained one of the few leadership figures that appealed to a wide cross-section of Islamists.

His repeated court appearances over the past four years evoked images of Omar Al-Mukhtar in his captivity: white-haired, wrapped in a white blanket; a frail old man who must yet be surrounded by heavy security.

Troubling questions

Akef seems to frighten the repressive regime in Cairo almost as much as the Italians were frightened by Al-Mukhtar. It has presided over four years of intense repression that includes as its victims tens of thousand of political prisoners, thousands of political exiles, and in its arsenal the widespread use of extra-judicial killings and systematic and pervasive torture.

Despite all this repression and semblance of control, the authorities refused to allow the funeral of an 89-year-old man to proceed on Friday. Only immediate family was allowed and the burial took place within hours of his passing.

Akef’s ordeal and ultimate death raise many troubling questions for both Egyptians and Westerners. What has become of the people of Egypt in the 85 years since Shawqi so eloquently eulogised Al-Mukhtar?

Where is the discourse of freedom, liberty and principle that made Shawqi’s poetry celebrated and Al-Mukhtar’s death an inspirational memory?

There were occasional muted calls for clemency for Akef, but little else. And over the course of the four years of his inhumane imprisonment, not a single Western government issued a statement opposing his incarceration or appealing for his release.

This silence, despite the fact that even by the laughable Egyptian standard of justice, he was acquitted on all charges in January 2016 and yet continued to be detained, for another 20 months, until his death.

The cost of silence

While Akef was the oldest political prisoner in Egypt, there are others in similar circumstances, whether because of age or health. Their ongoing detention, like the treatment Akef received both in life and in death, can only be described as reflecting the fright the Egyptian regime has of men and women who stand on principles.

Judge Mahmoud al-Khudeiri, one of the leading figures of the movement for an independent judiciary, continues to be imprisoned despite ailing health and advanced years.

But the silence of the international community towards the ongoing abuses in Egypt goes beyond the egregious cases of Akef and Al-Khudeiri. Human Rights Watch recently released a report on torture by Egyptian authorities, calling it endemic and possibly amounting to crimes against humanity. This silence by the international community is not without a cost.

It does not take much insight to realise that endorsing or financing the Egyptian regime invites the enmity of the people suffering its brutality or that repressiveness provides the perfect atmosphere for radicalisation.

Western democratic governments appear to have made the determination that the risk from this course of action is tolerable and the profits from continuing to embrace dictatorship far more desirable.

The assumption seems to be that the regime is unlikely to lose any time soon and that, even if it does, whoever replaces it will still crave the backing of the “international community” regardless of this deafening silence. This is far from a safe bet.

The better bet

This is a regime that prefers to assassinate young people than to bring them in court; that is holding an elderly woman in solitary confinement to put pressure on her even more elderly father; that has openly taken control of the judiciary; that has used the judiciary to issue mass execution sentences without consideration of individual cases; and that craves praise for releasing one activist as a “favour” to Donald Trump while continuing to indefinitely hold tens of thousands.

We now see that it is also a regime that feels threatened by an 89-year-old man not only in his dying days, but even at his funeral. This is a regime that understands that its hold on power is precarious and fears that every day might prove to be its last. We would do well to take note.

The events of the last few years have changed the people of the Middle East. In Egypt, Libya, Syria and Yemen, the old patterns have not held. If ever there was a time to bet on the people and not their oppressors this would be it.

Original Link: https://www.middleeasteye.net/fr/node/66261

Aug 21, 2017

Photo: People flee during the terror attacks in central Paris on 13 November 2015 (AFP)

Wael Haddara is an educator, associate professor of medicine at Western University, Canada, and a leader in the Canadian Muslim community. In 2012-2013, he served as senior advisor to President Mohamed Morsi of Egypt.

The spate of terrorist attacks in the UK have again brought to the fore a seemingly unresolvable debate. Is Islam to blame for the recent outbursts of violent extremism?

US President Donald Trump and those in his camp have an emphatic answer – yes – and fighting terror includes banning Muslims from entering the United States and potentially deporting those currently there.

But bigotry and xenophobia are a poor substitute for evidence-based analysis as a basis for sound policy. Decades of research on violent extremism have yielded empirical insights that can help us confront this terror far more effectively than fearmongering.

Attackers would not fit the bill

In a superficial sense, the connection to “radical Islam” is obvious. The perpetrators of attacks – in Manchester, London, Nice, Orlando and Paris – all paid some form of homage to Islamic State (IS). Some had travelled to Syria.

But they, and many others like them, would never pass muster amid the actual ranks of “Islamist militants”.

- Salman Abedi, the Manchester terrorist, was a party boy with a fondness for vodka Red Bull and weed

- Mohamed Bouhlel, the Nice attacker, had a history of petty crimes, “did not pray and liked girls and salsa”

- Omar Mateen, the Orlando shooter, and Salah Abdessalam, the Paris ring leader, also consumed alcohol publicly and regularly, and both were regulars at gay bars

- Mateen had profiles on several gay dating apps while Abdessalam was known as a gay “rentboy”

- Michael Zihaf-Bibeau, the gunman who shot dead a soldier in Canada’s capital, was a drug-addled petty criminal, who, like Abdessalam, had served time in jail

The personal history of many perpetrators of terrorist acts in Western countries fit exactly with that profile: troubled childhoods, lack of religious observance and occasional criminality. These features lead many in the Muslim community, as well as experts like Olivier Roy, to conclude that these terrorists are not “real” Muslims and that Islam is irrelevant to their violence.

Why self-belief matters

Research into “radicalisation” suggests there is no single path to radicalisation. An ideological foundation for violence as elaborated by Daesh (as Islamic State is often called) may be one factor.

But others are also important: political or social grievances; a lack of alternatives to pursue those grievances (for example, there was a sharp reduction in the appeal of violent groups in the aftermath of the Arab Spring and a sharp spike after the military coup in Egypt); and the means and resources to organise an attack; and, finally, individual factors.

One framework that can help us understand those individual factors is Terror Management Theory, developed by a group of American psychologists during the 1980s and validated by more than 400 empirical studies.

Terror Management Theory posits that because we all have a desire to live, the consciousness of our own mortality can lead to potentially paralysing existential terror. We may manage that terror by denying that we will die (“I’m too young” or “I’m too healthy” etc), but eventually we manage it by believing in our immortality; whether literal (belief in an afterlife) or symbolic (legacy, works etc).

But for this sense of immortality to succeed in mitigating the terror of dying, individuals must believe themselves worthy of those rewards and accolades.

In other words, for a belief in an afterlife or legacy to successfully relieve the terror of dying, one must have a sense of self-belief that the way one has lived one’s life is worthy of salvation or the adulation of fellow men.

People lacking in self-esteem, who have not effectively managed their terror of dying, respond by lashing out against others who do not share their cultural worldview.

For example, studies show that Americans, when reminded of their mortality or of 9/11, were more likely to agree with the use of extreme tactics to capture or kill Osama bin Laden, despite knowing those tactics would also kill thousands of innocent people, and would support the use of nuclear weapons against Iran.

Similarly Iranians, reminded of their mortality, were more likely to express support for suicide bombings against Americans. In both settings, control groups that were not exposed to the idea of dying responded in more tolerant and inclusive ways.

Phenomenon not unique to Islam

How does this inform the current debates? How does Islam fit into the equation?

To the extent that there is any religiosity, Abedi, Bouhlel and others demonstrate a classic profile of individuals with low self-esteem who have what Harvard psychologist Gordon Allport called “extrinsic religiousness” where religion serves as little more than a social group identifier.

Intrinsic religiousness describes religion as a part of who people are – an end in itself. Not surprisingly, intrinsic, but not extrinsic religiousness protects against hatred of, and lashing out at, other groups in Terror Management Theory studies.

This phenomenon is not unique to Islam and is consistent with an exhaustive report from the UK security service MI5 that a religious identity may actually protect against radicalisation.

In Terror Management Theory studies, priming subjects with positive verses from their holy texts – for example, “Do good to others because Allah loves those who do good” (Qur’an, 28:77) or “love your neighbour as yourself” – reduced the hatred toward, and lashing out against, others.

Bouhlel and those whose religious education derives primarily from IS propaganda cannot draw on that fund of spiritual enlightenment.

And so, in the face of personal crises – such as Abedi’s academic failure and increasing isolation and Bouhlel’s marital breakdown and financial problems – they may seek to regain their self-esteem through spectacular acts of terror.

The us-versus-them world

One part of the solution for mitigating the risk of terror may well be decent policy on both the domestic and foreign levels that reduces inequality, isolation and injustice.

The Islamic State, and troubled individuals, use religion to establish an us-versus-them world. Punitive security measures against Muslims reinforce this binary vision. Populists like Trump seem to be unaware of how they mirror the very narrative they claim to be fighting.

Their attacks, in turn, may spur a generation of young Muslims into approaching their faith, not as a path to spiritual and social fulfillment and enlightenment, but rather as an extrinsic identity that helps them assert their place in a hostile world. This plays right into the hands of IS narratives that reinforce exactly what Terror Management Theory studies warn against.

Much of the public seems to think that “radical Islam” is what causes terrorism. Yet the underlying psychology that leads to violence is about much more than just religion. The responsibility to stifle vicious fanaticism through inclusion and respect doesn’t just belong to Muslims, but to all of us.

Original Link: https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/why-terrorism-caused-much-more-just-religion

Feb 4, 2017

Ours is a beautiful country.

This may seem an odd thing to say given that we’ve just experienced one of Canada’s worst mass shootings. But it is true.

We are a stoic lot, we Canadians. But when tragedy strikes, there is an outpouring of solidarity that is life-affirming.

And so it was on Monday, not only in London, but across the country.

On Sunday night, a man walked into a mosque near Laval University in Quebec City, opened fire, killing six men while they prayed, and wounding many others. A mere hour later, I received a message from Rev. Kevin George, a friend who is rector at St Aidan’s Anglican Church. He was organizing a stand in solidarity at the London Muslim Mosque for noon the next day.

And with essentially a few hours’ notice overnight, hundreds of people — Christians, Jews and people of no particular religious affiliation — converged on the mosque at noon, on a workday, to offer support.

Friends have been posting their own stories of small acts of solidarity across the city. One hijab-wearing woman wrote about how she felt the silent well-wishes in people’s eyes at the grocery stores. Others wrote about strangers giving them hugs in the mall.

Ours is a beautiful country. But complacency will kill it.

In the 24 hours following the shooting, 14 hate crimes were reported in Montreal alone. Though this is an alarming spike, it is nothing new for Muslims, Jews, people of colour, those with disabilities, and any visibly different group. There has long been an ugly undercurrent.

And in recent years, that undercurrent has slowly but steadily become more visible, more mainstream and more effective. We should not deceive ourselves.

The hate we witnessed on Sunday night cannot be reduced to “Trumpism.” Trump has seized on a malevolent thread in our societies — but its existence predates him.

In fact, this is one area in which we can claim to have led the United States. Our last federal government excelled at dividing and isolating communities. Fear of Islam and Muslims became a strategy. Venerable institutions like the Senate were used to promote anti-Muslim pseudo-experts under the guise of advancing national security.

One such pseudo-expert immediately took to the blogosphere to claim the Quebec City massacre somehow involved a mosque leader, because he wasn’t there for prayer that night. Another right-wing media darling trolled the prime minister, calling him a coward for refusing to admit that the shooting was the work of “jihadis, not some white men.” And when the police concluded there was only one shooter, this person retweeted a claim that “the whitewashing begins.”

Those are not American trolls. They’re ours. And for years, even mainstream Canadian media outlets, under the guise of “hard-hitting investigative journalism” or “presenting alternate sides,” have given them a platform from which to spew their hatred.

If we are to combat this virulent strand of ugliness in our country, this has to stop.

The alleged Quebec City shooter was apparently known not only as pro-Trump and pro-Le Pen (the French far right extremist leader), but also anti-immigrant and anti-women.

And if we needed proof hate tends not to discriminate, on Monday, 13 Jewish community centres across North America received bomb threats. London’s own centre was evacuated because of one such threat.

The six men who died were a microcosm of Canadian society: a university professor, a butcher shop owner, government workers. Some were longtime residents, others newly arrived. This week is a time to honour their memory, stand in solidarity with their families and calm the frayed nerves of Canadians who are now very anxious about their personal safety.

Next week resumes the monumental task of ensuring this beautiful county we enjoy is the one we preserve and pass on to our children.

Wael Haddara is a London physician and educator.

Original Link: