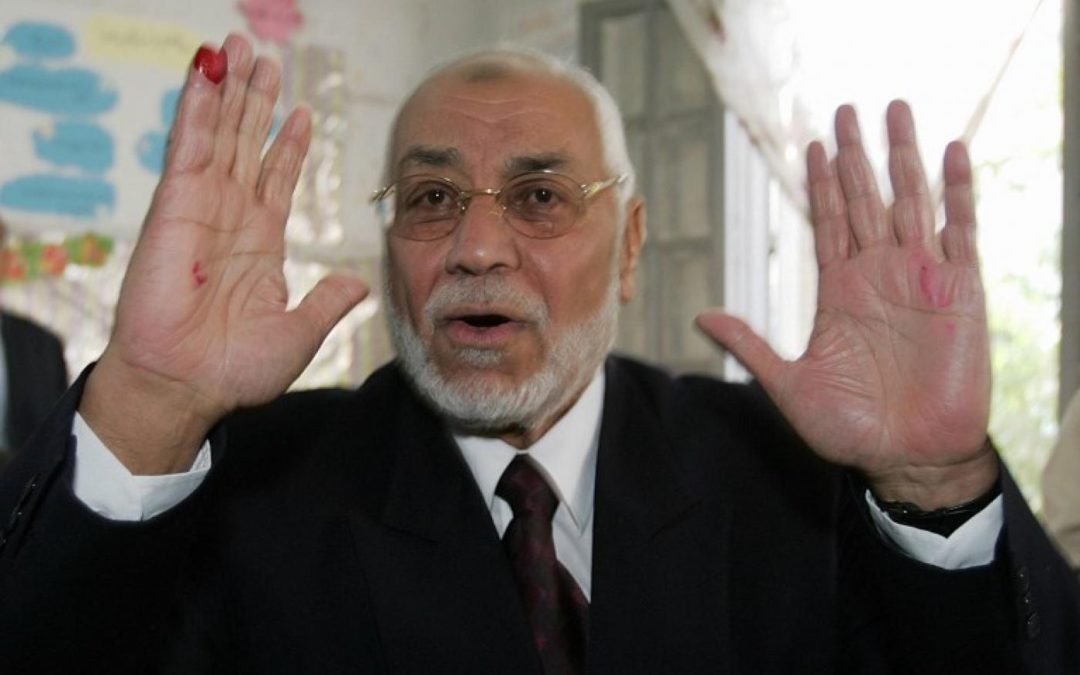

Photo: In November 2005, then Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohammed Mahdi Akef shows his finger, covered in ink after voting, as he walks away from a polling station a school in the populated suburb of Nasr City in Cairo (AFP)

Wael Haddara is an educator, associate professor of medicine at Western University, Canada, and a leader in the Canadian Muslim community. In 2012-2013, he served as senior advisor to President Mohamed Morsi of Egypt.

This month marks the 88th anniversary of the death of Omar Al-Mukhtar, the leader of the Libyan resistance to Italian occupation in the past century. Al-Mukhtar was executed for sedition by the occupying Italians on 16 September 1931.

In his famous eulogy of Al-Mukhtar, the celebrated poet Ahmad Shawqi predicted that his martyrdom would forever call Libyans to claim their freedom, and his blood would forever be an obstacle in the path of reconciliation between the occupier and the occupied.

It is a measure of the power of ideas and the impact of human resistance that when Al-Mukhtar was finally captured, at 73 years of age, the Italians chose to conduct his trial in secret and to bury him in an unmarked grave, guarded by an Italian sentry.

Oppressors are afraid of ideas, and of the men and women who believe in them, regardless of their frailty, advanced age or even whether they are dead or alive.

The frail man surrounded by security

This month also marks the death of another man, Mohammad Mahdi Akef. He was a former Egyptian parliamentarian, and the seventh man to serve as the general guide of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood.

Under his leadership in 2004, the Muslim Brotherhood issued the first truly comprehensive reform programme in Egypt, and in 2005 led the Muslim Brotherhood to its largest electoral victory prior to the 2011 Revolution.

In 2009, he was ranked as #12 in the 500 most influential Muslims, selected by scholars for a book issued by the Royal Islamic Center for Strategic Studies.

Following the overthrow of President Mohamed Morsi in 2013, he was arrested at the grand old age of 85 years and held, like many of Egypt’s 40,000 political prisoners, under brutal conditions.

According to his family, he was diagnosed with cancer last year, and despite declining health, was held, nearly incommunicado, by the Egyptian regime.

Akef was widely celebrated for refusing to be nominated for a second term as the Brotherhood’s guide, vacating the post in 2010 after the election of Muhammad Badie and he remained one of the few leadership figures that appealed to a wide cross-section of Islamists.

His repeated court appearances over the past four years evoked images of Omar Al-Mukhtar in his captivity: white-haired, wrapped in a white blanket; a frail old man who must yet be surrounded by heavy security.

Troubling questions

Akef seems to frighten the repressive regime in Cairo almost as much as the Italians were frightened by Al-Mukhtar. It has presided over four years of intense repression that includes as its victims tens of thousand of political prisoners, thousands of political exiles, and in its arsenal the widespread use of extra-judicial killings and systematic and pervasive torture.

Despite all this repression and semblance of control, the authorities refused to allow the funeral of an 89-year-old man to proceed on Friday. Only immediate family was allowed and the burial took place within hours of his passing.

Akef’s ordeal and ultimate death raise many troubling questions for both Egyptians and Westerners. What has become of the people of Egypt in the 85 years since Shawqi so eloquently eulogised Al-Mukhtar?

Where is the discourse of freedom, liberty and principle that made Shawqi’s poetry celebrated and Al-Mukhtar’s death an inspirational memory?

There were occasional muted calls for clemency for Akef, but little else. And over the course of the four years of his inhumane imprisonment, not a single Western government issued a statement opposing his incarceration or appealing for his release.

This silence, despite the fact that even by the laughable Egyptian standard of justice, he was acquitted on all charges in January 2016 and yet continued to be detained, for another 20 months, until his death.

The cost of silence

While Akef was the oldest political prisoner in Egypt, there are others in similar circumstances, whether because of age or health. Their ongoing detention, like the treatment Akef received both in life and in death, can only be described as reflecting the fright the Egyptian regime has of men and women who stand on principles.

Judge Mahmoud al-Khudeiri, one of the leading figures of the movement for an independent judiciary, continues to be imprisoned despite ailing health and advanced years.

But the silence of the international community towards the ongoing abuses in Egypt goes beyond the egregious cases of Akef and Al-Khudeiri. Human Rights Watch recently released a report on torture by Egyptian authorities, calling it endemic and possibly amounting to crimes against humanity. This silence by the international community is not without a cost.

It does not take much insight to realise that endorsing or financing the Egyptian regime invites the enmity of the people suffering its brutality or that repressiveness provides the perfect atmosphere for radicalisation.

Western democratic governments appear to have made the determination that the risk from this course of action is tolerable and the profits from continuing to embrace dictatorship far more desirable.

The assumption seems to be that the regime is unlikely to lose any time soon and that, even if it does, whoever replaces it will still crave the backing of the “international community” regardless of this deafening silence. This is far from a safe bet.

The better bet

This is a regime that prefers to assassinate young people than to bring them in court; that is holding an elderly woman in solitary confinement to put pressure on her even more elderly father; that has openly taken control of the judiciary; that has used the judiciary to issue mass execution sentences without consideration of individual cases; and that craves praise for releasing one activist as a “favour” to Donald Trump while continuing to indefinitely hold tens of thousands.

We now see that it is also a regime that feels threatened by an 89-year-old man not only in his dying days, but even at his funeral. This is a regime that understands that its hold on power is precarious and fears that every day might prove to be its last. We would do well to take note.

The events of the last few years have changed the people of the Middle East. In Egypt, Libya, Syria and Yemen, the old patterns have not held. If ever there was a time to bet on the people and not their oppressors this would be it.

Original Link: https://www.middleeasteye.net/fr/node/66261